The “Physiognomy” of MBTI Tests in the Workplace – Can Personality Digitization Become a “New Threshold” for Recruitment?

https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1K94y1V72z/?spm_id_from=333.337.search-card.all.click

The controversy detailed in the linked report—involving a Beijing-based, publicly listed internet company—has ignited a broader debate over the fairness of MBTI testing. According to a report by Legal Daily on November 20, 2024, Lin Lin (a pseudonym), a 26-year-old job seeker, successfully passed the first four rounds of traditional interviews for a fund management position but was rejected in the final AI personality test because she was identified as an MBTI “Guardian” (ISFJ). The HR department explicitly stated that “ISFJ-type personnel are not needed” and cited this as the sole reason for the rejection. The incident, after being reported by the media, immediately sparked heated debates in the workplace and among various sectors of society.

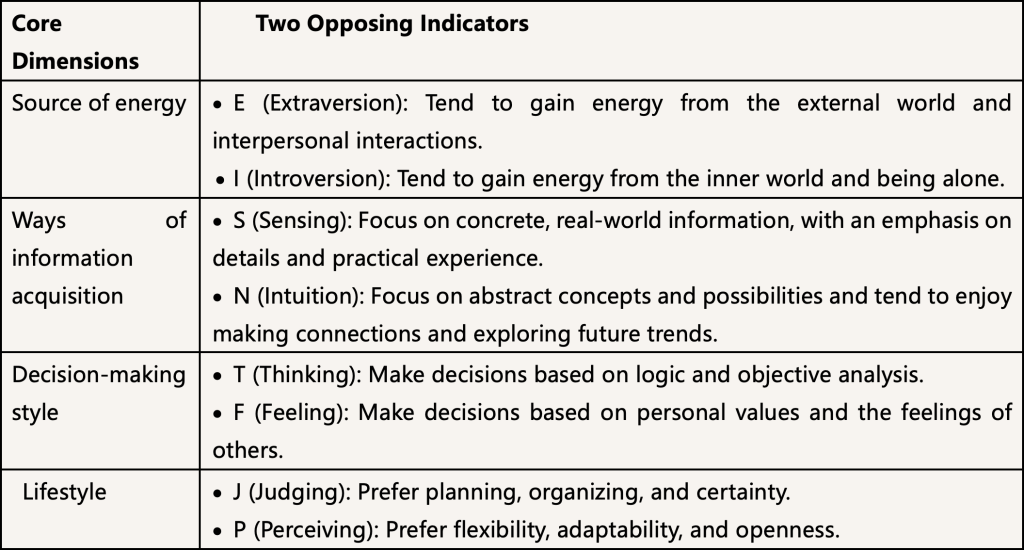

MBTI (Myers-Briggs Type Indicator) is a personality classification tool based on Carl Jung’s theory of psychological types. It combines different personality types through four dimensions, with each dimension having two opposing indicators, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Two-Opposing Indicators of Core Dimensions

The above core dimensions are combined in different arrangements to form 16 personality tendencies, each represented by a four-letter combination. Each type has its unique personality traits and areas of strength, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The 16 Personality Types

- ISTJ (Logistician): Practical, responsible, and well-organized, with a focus on rules and traditions.

- ISFJ (Defender): Warm, loyal, and meticulous, skilled at taking care of others.

- INFJ (Advocate): Idealistic and insightful, pursuing meaning and depth.

- INTJ (Architect): Independent, rational, and far-sighted, adept at long-term planning.

- ISTP (Virtuoso): Calm and flexible, skilled at hands-on problem-solving.

- ISFP (Adventurer): Gentle and artistic, emphasizing present experiences.

- INFP (Mediator): Sensitive and idealistic, valuing personal values.

- INTP (Logician): Curious and analytical, passionate about theories and innovation.

- ESTP (Entrepreneur): Confident and action-oriented, good at adapting to changing situations.

- ESFP (Entertainer): Enthusiastic and optimistic, enjoying socializing and entertainment.

- ENFP (Campaigner): Passionate and creative, skilled at motivating others.

- ENTP (Debater): Witty and challenge-loving, fond of exploring new perspectives.

- ESTJ (Executive): Efficient and practical, adept at organizing and leading.

- ESFJ (Consul): Friendly and responsible, focusing on harmony and collaboration.

- ENFJ (Protagonist): Charismatic and empathetic, skilled at guiding others.

- ENTJ (Commander): Decisive and strategic, a natural leader.

In recent years, the use of MBTI personality tests in recruitment has become increasingly widespread, even emerging as a “hard screening criterion” for some enterprises. Over 60% of Fortune 500 companies incorporate MBTI into their interview processes or consider it as a factor, with some requiring job seekers to submit test reports. For instance, a well-known internet company uses MBTI assessments in its recruitment to identify top talent with innovative spirit and teamwork skills; some enterprises specify preferred MBTI types based on job requirements—such as seeking ENFJs for management roles and ISTJs for finance positions—to enhance team compatibility, reduce communication costs, and improve recruitment efficiency. However, in reality, once digitized personality profiles derived from MBTI tests become a “new threshold” for recruitment, they bring forth numerous ethical challenges.

First, MBTI personality tests carry a significant risk of misjudgment. Personality is fluid and context-dependent. A 2018 study in the Journal of Personality Assessment noted that the test-retest consistency of the MBTI stands at only around 50-60%, far lower than that of commonly used clinical scales (typically over 80%). This is because we often respond based on our “ideal self” rather than our actual behaviors. For instance, if my recent work has involved collaborating with multiple people in a team, the test result might come out as ISFJ; yet if I’ve been leading a project lately, the result could shift to ENTJ. These two outcomes would translate to entirely different levels of job fit in the recruitment process.

Second, reducing complex personalities to “label-based” categorizations can reinforce stereotypes. Human personality is continuous, multidimensional, and dynamic. The two-dimensional division of core dimensions in Table 1 overlooks the uniqueness of each individual, leading to a flattened understanding of individual differences. For example, we may gradually equate “introversion” with “poor social skills” and ISFJ with “lack of creativity.” When job seekers internalize a certain type of label, they may unconsciously amplify behaviors that align with that label. More seriously, stereotypes derived from data-driven decisions can solidify prejudices, amplify structural discrimination, and ultimately result in employment injustice.

Third, the phenomenon of the “assessment black box” constitutes multiple infringements on job seekers’ rights. Take Lin Lin’s case as an example: when she asked the company to explain the specific basis for deeming the ISFJ type incompatible with the position, the company refused to disclose the evaluation criteria and algorithm logic on the grounds of protecting trade secrets. This practice of fully monopolizing the right to interpretation essentially deprives job seekers of their right to know and right to appeal. Moreover, by packaging subjective personality judgments as objective algorithmic conclusions, companies may encode hidden biases into so-called “scientific standards.” Meanwhile, the neutrality of technology becomes a tool for shirking responsibility—HR departments attribute decisions to the system, and developers shift blame to the company’s employment standards, creating a typical vacuum of accountability. Such an opaque assessment mechanism not only violates privacy rights but also easily sparks public doubts about the fairness of the tests, ultimately damaging the company’s social reputation and credibility.

Fourth, the quantification of personality into data objectifies human character and inflicts psychological harm on job seekers who face setbacks. The so-called “scientific evaluation systems” constructed by enterprises essentially constitute a form of hidden algorithmic violence—rich, multi-dimensional personality traits are crudely reduced to one-dimensional data symbols, and vivid personalities are alienated into parameters processable by algorithms. In Lin Lin’s case, the mechanical judgment that she belonged to an “unwanted personality type” not only demeans human dignity but also reveals the algorithmic evaluation system’s disregard for the complex nature of humanity. Such “authoritarian algorithms,” which reduce human worth to binary judgments, are committing violence under the guise of science, and the psychological trauma they inflict on job seekers is all the more insidious and destructive.

In today’s diverse recruitment landscape, we should embrace differences with an open and inclusive spirit, and understand each unique soul with empathy. Rather than fixating on digitized personalities, we ought to build talent selection mechanisms that truly respect the diversity of human potential—so that candidates with varied backgrounds, experiences, and traits all get a fair shot at growth.

Look closely: HR professionals are wielding a 16-type personality magnifying glass, playing a game of “workplace match-up.” Are you their “chosen one” in this game? The talent market was never a match-three puzzle board. When an INFJ’s insight collides with an ESTP’s drive, when an ISTJ’s precision meets an ENFP’s creativity—these seemingly conflicting trait combinations are precisely the workplace’s most precious “hidden blind boxes.” We’ve confused screening with selecting the best, failing to see that the “fragments” we cast aside could cost companies countless possibilities.